Rediscovering the Lure of North Carolina's

Hickory Nut Gorge Area

[originally published as a Backroads Tour in July/August 1999 Blue Ridge Country]

My home community of Fairview, NC, impressed me again last April. On a warm evening after work, I finished a short run on a woodsy back road as clouds turned pink in the west. I jumped in my truck and raced to a pasture, where I set up my camera for the twilight moon. I suddenly realized that I was enjoying as fine a setting as any popular recreation area, just four minutes from home.

I’ve roamed my local mountains since I was five. Only recently did I notice how perfectly the area complements the nearby towns of Montreat, Chimney Rock, and Flat Rock. Unlike many natural areas, the landscapes here are either privately owned or preserved to look that way. The unique stamp of original owners remains on properties they were able to inhabit without overwhelming.

Eight miles from the Blue Ridge Parkway, US 74-A heads east into a straightaway where tall peaks with names like Tater Knob and Buzzard’s Roost rise from the pastures and cornfields of one of Fairview’s major valleys. After a few switchbacks, casual travelers can easily overlook the long white house sandwiched between Ferguson Mountain and a horse pasture. A roadside marker simply reads "Sherrill’s Inn," with a twenty-word description that hardly does justice to a site that already brimmed with history in 1916.

Jim and Elizabeth McClure came through Fairview that year on a spontaneous honeymoon that made them feel more like gypsies than upper-middle class northerners. As they snaked toward Hickory Nut Gap, they were smitten by the old inn on the hill. They took their admiration further than most travelers by pulling up to the house, finding the owner, and offering a lease that was finalized in the Buncombe County deed books less than two months later.

|

Jamie and Elspeth Clarke at Sherrill's Inn, Hickory Nut Gap, Fairview, 1998. |

John Ashworth had first bought the property in 1797, building a cabin and fort before selling everything to stagecoach driver Bedford Sherrill. Sherrill expanded the cabin for his tired travelers and later added a stockyard for drovers with herds bound for South Carolina markets. Sherrill’s Inn survived the Civil War, changed hands twice, enjoyed more years of tourism, changed hands twice again, and became a mildly neglected farm by the time the McClures arrived.

What was intended as a temporary dwelling soon became a home the couple couldn’t leave. Elizabeth transformed the property with boxwoods, flower gardens, and outbuildings for hired hands. Jim pushed the farm to relieve World War I food shortages. Within four years, he went on to organize a Farmer’s Federation that merged his disorganized, disheartened, and oft-cheated neighbors into a bold competitive coalition. His natural gift for making friends and uniting strangers kept his vision going for the next forty years.

These days, their daughter Elspeth lives in the inn with husband and former U.S. Congressman Jamie Clarke [Jamie Clarke died in April 1999, and Elspeth in November 2001]. Any given day can turn up their own sons and daughters, local friends, or guests from as far away as France and Kenya. In a time when trendy people turn to increasingly contrived methods of forcing leisure into hectic schedules, this family continues a tradition of generating instant fun in any circumstance. Quaint outdoor square dances, covered-dish suppers, and Christmas caroling are still common at the inn, even as community names and faces change. As Jim McClure’s biographer and grandson-in-law, John Ager, noted, "Life at Hickory Nut Gap Farm has nothing to do with the search for a utopia, and everything to do with the acceptance and enjoyment and encouragement of people in all their variety."

Two miles past the inn, on a highway that follows roughly the same route as Bedford Sherrill's stagecoach, Bearwallow Mountain Road heads up to Bearwallow Gap. Here, hikers can climb a mile on a gated private road to a USFS fire tower on the 4,232-foot mountain.

Bearwallow makes a great outing on chilly winter days when the Parkway stays icy and Forest Service roads are closed. Fast walkers can be on the blustery summit in 15 minutes, without the hassle of determining which public lands are open and accessible. Clear air enhances views of Fairview’s farms and forests in the west and Hickory Nut Gorge in the east.

Back in the valley, 74-A passes through Gerton and drops into a gorge full of craft shops and fruit stands. In five miles it enters Bat Cave, the town, below Bat Cave itself. Here, NC 9 heads left toward Black Mountain and Montreat, while US 64 turns right toward Hendersonville and Flat Rock.

|

Tom Lawter and Sarah Lawter at their Bat Cave Apple House. |

The Gorge’s most remarkable feature looms two miles past this junction. Chimney Rock, a 315-foot granite remnant of 500 million year-old igneous rock, stands like a medieval watchtower over the Rocky Broad River. On clear mornings, first light turns gray cliffs golden before dropping into green forest. Four-hundred-foot Hickory Nut Falls, the tallest in the East, hangs over the Rocky Broad like a lesser Yosemite Falls over the Merced.

The rock and 1,000 surrounding acres are preserved as a private attraction that owes its existence largely to one man’s vision. Born in Missouri in 1871, Lucius B. Morse was a practicing physician before contracting tuberculosis and seeking a healthier climate in North Carolina. He loved the mountains, especially Chimney Rock. The original owner opened a public trail and stairs, but Morse had bigger plans, and with the help of two brothers he purchased the mountain for $5,000 in 1902.

By 1916, the men had bridged the river and cut a three-mile road to the Rock. The great flood of the same year destroyed parts of the project, but they rebuilt quickly, eventually adding a gatekeeper’s lodge, 3-story dining hall, and offices and parking lots. Perhaps the most exotic feature was a 258-foot elevator shaft that now whisks visitors to the summit in less than a minute, shortcutting an alternate system of stairs from the base.

At least in superficial ways, Morse’s life parallels Jim McClure’s. Morse sought in the mountains a reprieve from TB; McClure hoped for a cure of the stress-related "congestion of the brain" he’d suffered up North. The 1916 flood wiped out Morse’s early park developments; across the Gap, McClure was fighting his way on washed-out roads to secure his lease on Sherrill’s Inn. Morse visualized the potential of his mountain as a popular park just as McClure saw the financial possibilities of local farmland. Chimney Rock is a bit more commercial than most public parks, but the natural beauty remains as surely as both McClures’ amiable personalities survive at Hickory Nut Gap Farm.

|

The Rocky Broad River below Chimney Rock. |

The main road continues into Lake Lure, a ritzy resort town clustered around a reservoir of the same name. High cliffs make an impressive backdrop for fishing and paddle boating, but more traditional Appalachian experiences await elsewhere. Back in Bat Cave, State Highway 9 winds north through 18 miles of fine mountain scenery before entering one of the classiest little towns in western North Carolina.

Named for the highest peaks in the East, Black Mountain was traditionally a tourists’ gateway to Mt. Mitchell. A Mrs. S. P. Taber Willets, of New York City, described her 1901 "tour" in terms that sound considerably more adventurous than the hikes of today's hardy backpackers. After riding the train partway from Asheville, Mrs. Willets followed a rough path among "towering mountains" and the North Fork of the Swannanoa River before finally reaching a farmhouse at twilight. Her generous host led her to Mitchell’s base in the morning, where she followed a wiry, elderly guide on a trail that "became more steep and obscure, [curving] like a snake in and out among the broken rocks ... a tortuous path it was, climbing upward for miles." After a chilly night on an evergreen-bough bed under an overhang near the summit, Mrs. Willets contentedly descended through Black Mountain to Asheville.

The valley was never the same after thirsty Asheville dammed the North Fork for a water supply. Locals born under the tall peaks found themselves unable to even visit the family lands from which they were evicted. In 1954, F. Bascombe Burnette ended a piece for the Black Mountain News by resigning that, "It surely grieves me to look up old North Fork ... Such is life. There is nothing we can do about it."

Now, the Blue Ridge Parkway skirts the valley at 5,000 feet. "No Stopping" signs between mileposts 355 and 370 keep human impact to a minimum, protecting the 15,000-acre watershed’s rare WS-1 water quality rating (reserved for natural and undeveloped areas only). All around is an alpine paradise matched only in the Balsam Mountains farther south, while at night, the lights of Black Mountain twinkle beyond a bowl of darkness above the Burnette Reservoir. The old property rights argument is placed in bold relief here, but it is no easier to grapple with. Despite any sympathies for original owners, this wild pocket of uninhabited land is plenty refreshing.

From Highway 9, Black Mountain itself seems busier than ever. The "Front Porch of Western North Carolina" includes a downtown chock full of art and craft galleries, music clubs, and antique and factory stores. Beautiful scenery, a pleasant climate, and easy accessibility has made the area popular for summer camps and religious conference centers.

One "center" deserves special mention. Straight ahead on 9, the town of Montreat was envisioned in the late 1890s as an interdenominational assembly of houses, schools, libraries, orphanages, and other facilities for "Christian work and fellowship." Now affiliated with the Presbyterian Church and boasting its own college, it remains a model community. Narrow roads curl among shady creeks and houses nestle in rhododendrons. Buildings made from local rock and timber harmonize with the forest. Reverend R. C. Anderson summed up the community’s spirit in his 1947 The Story of Montreat from its Beginning: "When we see the majestic oak or the chestnut or the pine, we think of Him who put the life in the little acorn or the chestnut. We think of the soil into which the seed found nourishment, the properties or the elements of the atmosphere and the ingredients and the fertility of the ground that caused the little germ to sprout...until it becomes the hardened wood that makes the temple in which we worship, the house in which we dwell."

Much of the land remains forested, and hikers are welcome on miles of strenuous trails that climb high peaks like Greybeard Mountain (5,360'), Big Slaty Mountain (4,855'), Brushy Mountain (3,855'), or Lookout Rock (3,760'). Viewed from craggy outcrops, the Montreat properties blend perfectly with huge tracts of Pisgah National Forest, the Asheville watershed, and the Parkway corridor. Visually, at least, the area may be better off than at Montreat’s beginning, when logging trains occasionally set fire to the woods as they carried fresh Mt. Mitchell timber over the property to Black Mountain.

|

Looking toward the Black Mountains from Greybeard Mountain, Montreat. |

Instead of Highway 9, drivers can take US 64 east from Bat Cave along Reedypatch Creek. Here, fields, orchards, and an array of produce stands hint of the 52,000 acres that put Henderson County 5th in the state's agricultural cash receipts. A few of the dozen miles from Bat Cave to Hendersonville look more like Midwest farm country than the southern Appalachians.

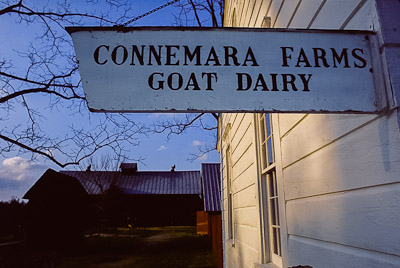

Highway 64 junctions with US 25 in Hendersonville, where brown signs lead 6 miles to the Carl Sandburg Home in Flat Rock. Now a National Historic Site, "Connemara" belonged to the secretary of the Confederate treasury and a textile baron before the Sandburgs moved in in 1945. The spacious grounds satisfied the famous writer’s need for solitude, while the big house kept his 12,000 books within easy reach.

Sandburg’s granddaughter, Paula Steichen, offers a personal view of the man who won Pulitzer Prizes, worked with Presidents, kings, and movie stars, and suffered criticism for his Socialist leanings. In My Connemara, she remembers Grandfather "Buppong" talking to trees, singing with children, and making light of his own poem, "Fog," during the height of its popularity: "De fog come on itti bitti kitti footsies...".

She also reveals the Sandburg who took walks in the dead of night and collected acorns and bits of wood for the house. A mile away on Big Glassy Mountain, he could look out on Hendersonville, the Blue Ridge, and beyond. Surely his mountains were on his mind when he said, "A man must find time for himself...to go away by himself and experience loneliness; to sit on a rock in the forest and to ask of himself, ‘Who am I, and where have I been, and where am I going?’"

For all Sandburg’s popularity, Connemara was more than a home for a famous writer. His wife Lilian and daughter Helga built reputations on their Chikaming goats, selling milk throughout the Southeast and shipping animals to breeders. Lilian pored over lineages and planned breeding strategies at her desk, eventually producing a Toggenburg doe that became the all-breed American champion in milk production. Her success led at least one would-be admirer to ask, "And what does your husband do?"

|

Carl Sandburg estate. |

The Park Service has preserved the house to look as if the family went out walking only minutes ago. Each room still reveals personalities: Carl’s simple tastes are evident in the crate he used for a living room end table, and Lilian’s orderliness is displayed in the tidy work space that greatly contrasts her husband’s office pigsty.

Mostly, the woods and trails of Connemara make it clear this family appreciated their mountains. Certainly anyone with their energy and imagination could have turned the quiet woods into some profitable enterprise. Thankfully they chose forest over finances, and the Sandburgs' Connemara joins the McClures' Hickory Nut Gap Farm, Lucius Morse’s Chimney Rock, and the Presbyterian Church’s Montreat in testifying of owners who recognized the value of leaving some of their lands unaltered long before environmentalism was in vogue.

©Stephen Schoof